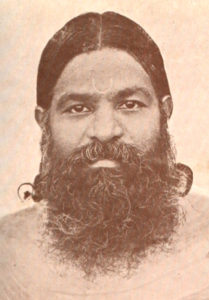

V. V. S. Aiyar (1881-1925)

“… The noble story of thy life must for the time being, nay, perhaps for all time to come, remain untold. For while those who can recite it are living, the time to tell it may not come, and when the time comes, when all that is worth telling will no longer remain suppressed and will eagerly be listened to, the generation that could have recounted it might have passed away. Thy greatness, therefore, must stand undimmed but unwitnessed by man like the lofty Himalayan peaks. Thy services and sacrifices must lie buried in oblivion as do the mighty foundations of a mighty castle….” Vinayak Damodar Sarvakar in 1925

Varahaneri Venkatesa Subramaniam Aiyar was born to a middle class family of Tiruchi on 2 April 1881. He was 44 years old when he died on 3 June 1925. It was a relatively short life. He will be remembered both as an early Tamil revolutionary and as the father of the modern Tamil short story. R.A. Padmanabhan writes in his biography of V.V.S.Aiyar:

“It has been said that the all round revival of the Tamil country in the first two decades of the century owes much to three brilliant sons of Tamil Nadu, Poet C.Subramania Bharathi, Scholar-Revolutionary V.V.S.Aiyar and Swadeshi Steamship hero, V.O.Chidambaram Pillai.

They were all dedicated patriots working with a passion, each in his chosen field for the liberation of Bharatmata. All the three were imbued with a strong love of the Tamil language and the culture of the Tamil people. Each contributed his own quota to boost the self esteem of the Tamils… Whilst the names of Bharathi and Chidambaram Pillai are familiar to present day India, it cannot be said that it is equally familiar with the name of V.V.S.Aiyar.”

Subramaniam passed the Pleader’s Examination in Madras in the First Grade in 1902 and thereafter practised as a Pleader in the District Court of Tiruchi. In 1906, he went to Rangoon, and practised as a junior in the Chambers of an English Barrister whose clientele included a number of Tamil businessmen who were resident in Burma. From Rangoon, he left for London in 1907, enrolled in Lincoln’s Inn with a view to becoming a Barrister at Law. It was in London, that V.V.S.Aiyar together with Vinayak Damodar Sarvakar, began to take an active role in the militant struggle for Indian independence.

In 1910, Aiyar resigned his membership of Lincoln’s Inn. A warrant was issued by the British for his arrest and Aiyar escaped to Paris. But he had no wish to remain in Paris as a political exile. He returned to India, albeit to French Pondicherry, and there met with both Subramaniya Bharathi and Aurobindo. He remained in Pondicherry for ten years until after the end of the first World War. It was during this period that he translated the whole of the Thirukural into English. In his Preface to the Second Edition of his ‘Maxims of Thiruvalluvar’, Aiyar declares the reasons that led him to write::

“When, soon after the Great War broke out, the (German battleship) Emden was scouring the Bay of Bengal, some members of the secret police force stationed by the British Indian Government at Pondicherry to watch the movements of the Indian refugees thought it a golden opportunity to rise in the service by connecting the latter with the activities of the Emden. It is said that as a result of their plot, the Madras Government desired the then Governor of Pondicherry to banish the Indian political refugees to Africa. Anyway, the French police brought several charges against these refugees among whom was Shriman Aiyar. These cases, however, failed ignominiously. In spite of that, the then Governor of Pondicherry wished to deport them to Algeria. He however, wanted that it should not appear that he forced them to leave Pondicherry. He, therefore sent messengers to them who threatened them unofficially with all sorts of dire consequences if they did not voluntarily leave for Algiers. The negotiation lasted for about four or five months. As soon as the negotiation started, Shriman Aiyar thought that the French Government might any day force him out of Pondicherry, and wanted to leave something behind him which might keep his memory green among his countrymen even though his body should be removed by force out of the Tamil land which he loved so dearly.

He therefore set about to think as to what would be the best thing for him to do under these circumstances, taking into consideration the very short and precarious period of time at his disposal. It did not take him long to decide that if he could translate into English the shortest and at the same time the most perfect of the ancient Tamil classics, he could claim a small corner in the memory of his countrymen. He therefore set to work at it at top speed.

It was about the 1st of November, 1914 that he put pen on paper. Day after day he pounded away at the translation, every evening thinking that the next morning he might receive a peremptory order to leave Pondicherry. This sword of Damocles ever hanging above his head only made him determined to work at white heat, so that in case he had to leave India he might leave as large a number as possible of the maxims worthily translated. He went on with his translation with so much ardour that even while his house was being searched by the French police for discovering if he had concealed in his house a fugitive from justice, he put his hand to the translation the moment the police left his study to search the other parts of his house. He was a happy man when on the 1st of March 1915 the last lines of the preface were fair copied and the whole book was ready for the press…”

After the end of World War I, V.V.S.Aiyar returned to Chennai and functioned as the Editor of the journal Desabhaktan. In September 1921 he was arrested for sedition and sentenced to 9 months imprisonment. And it was in prison that V.V.S.Aiyar wrote his magnum opus – a study of Kamban’s Ramayana.

V.V.S.Aiyar drowned in the Papanasam Falls in June 1925 in circumstances which remain controversial. On his death, Vinayak Damodar Sarvakar, Aiyar’s comrade in arms, paid a moving tribute in the journal, Mahratta:

“Heavy griefs have often embittered our life; but none heavier than what thy sudden death caused, oh friend, ever taxed our capacity to endure. Memories of those momentous years and trying days rise in a flood and, struggling to find a vent, keep knocking at the gates of our heart. How we wish we could have spoken of them all and recited our reminiscences. But our lips must remain sealed. How we long to write of the goodness and gentleness of disposition – how when betrayed thou stood unshaken, how thou served them who owned thee not and how thou suffered when unbeknown and modest, and made not the slightest mention of it when thou got known – how we long to write of it all. But our pen is a broken reed. The noble story of thy life must for the time being, nay, perhaps for all time to come, remain untold. For while those who can recite it are living, the time to tell it may not come, and when the time comes, when all that is worth telling will no longer remain suppressed and will eagerly be listened to, the generation that could have recounted it might have passed away. Thy greatness, therefore, must stand undimmed but unwitnessed by man like the lofty Himalayan peaks. Thy services and sacrifices must lie buried in oblivion as do the mighty foundations of a mighty castle.

The news of thy sudden death was bitter enough. But bitterer by far is this, our inability to relate to posterity under what heavy obligations thou hast placed them and to express the fullness of our personal and public grief.

For indeed he was a pillar of strength, a Hindu of Hindus, and in him our Hindu race has lost one of the most exalted representatives and perfect flower of our Hindu civilisation – ripe in experience, and mellowed by sufferings and devoted to the service of men and God, the cause of the Hindu Sanghatan was sure to find in him one of its best and foremost champions in Madras.

In 1907 or somewhere there, one day the maid-servant at the famous India House in London handed a visiting card to us as we came downstairs to dine and told us a gentleman was waiting in the drawing room. Presently the door was flung open and a gentleman, neatly dressed in European costume and inclined to be fashionable, warmly shook hands with us. He told us he had been a pleader at Rangoon and had come over to England to qualify himself as a full-fledged barrister. He was past thirty and seemed a bit agreeably surprised to find us so young. He assured us of his intention to study English music and even assured us that he was eager to get a few lessons in dancing as well. We, as usual, entered our mild protest against thus dissipating the energy of our youth in light-hearted pastimes when momentous issues hung in the balance. The gentleman, unconvinced, though impressed, took our leave promising to continue to call upon us every now and then. He was Srijut V.V.S. Aiyar.

In 1910, somewhere in March, we stood as a prisoner, then only very recently pent up in Brixton, the formidable prison in London. The warder announced visits; anxiously we accompany the file of prisoners to the visiting yard. We stand behind the bars wondering who could have come to call on us and thus invite the unpleasant attention of the London Police. For to acknowledge our acquaintance from the visitor’s box in front of the prison bars was a sure step to eventually get behind them. Presently one dignified figure enters the box in front of us. It was V.V.S. Aiyar. His beard was closely waving on his breast. He was unkempt. He was no longer the neatly dressed fashionable gentleman. His whole figure was transformed with some great act of dedication of life. ‘Oh leader !’ he feelingly accosted us, ‘Why did you leave Paris at all !’ We soothingly said, ‘What is the use of discussing it here? Rightly or not I am here, pent up in this prison, and the best way now is to see what is to be done next, how to face the present.’

While fully discussing the future plans, the bell rang and the warders came rushing and shouting unceremoniously, ‘Time up !’ With a heavy heart we looked into each other’s eyes. We knew it would perhaps be the last time we ever saw each other in this life. Tears rose. Suppressing them, we said, ‘No ! we are Hindus. We have read the Gita. We must not weep in the presence of these unsympathetic crowds.’ .. We parted. I watched till he disappeared and said to my mind, ‘Alas ! It is well nigh impossible to see this loving soul again .’ For one of two fates was certain to fall to my lot, the gallows or the Andamans and neither could hold any prospect before me of seeing my friends again.

This was in 1910. Fourteen years rolled by, and the impossible actually happened. Travelling the most dangerous and meandering by-paths and by-lanes and subterranean passages of life, so formidably bordering the realms of death, I met Srijut Aiyar a couple of months ago. He had travelled all the distance from Madras to Bombay to enable us to revel a few hours in the wine of romantic joy. We forgot for a while the bitterness and the keen pangs of the afflicted and the tortured past and lightly gossiped as boys fresh from school meeting after a long holiday. He took my leave. I watched him disappear and said to my mind ‘Now I can call him again any time I like.’

Little I knew then that he was to disappear beyond all human recall. When human wisdom shook its head and snorted out ‘Impossible!’, events proved it possible and when it gaily assured itself, ‘At any time,’ Destiny put in a stern ‘Never!’ Thus our Fate seems to act with no nobler intention than to mock and humiliate human calculations!

With Aiyar the politician we cannot concern ourselves here. It is the loss of Aiyar, the scholar, the friend, the noblest type of a Hindu gentleman, the author of Kural (in translation), the saintly soul whose life has been one continuous sacrifice and worship, that we so bitterly bewail today and bitterly chafe at our inability to pay a public tribute to his memory in a fashion worthy of the noble dead. Oh, the times on which our generation has fallen! The noblest sink down and are washed off to the shores of death, while the unworthy keep gaily swimming on the tides of life.

But thou hast done thy duty, friend! It was for Human Love that thou lived, and died too for human love as martyr unto her.

Thou knew no peace in life, oh Soldier of God. But peace be with thee in Death. Oh friend, peace be with thee and divine rest!”

Ref: Tamil Nation

Leave a Reply